By Brian Handwerk on November 11th, 2005 on news.nationalgeographic.com

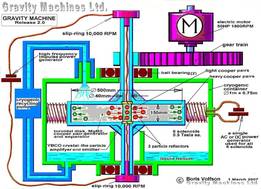

A perpetual-motion machine may defy the laws of physics, but an Indiana inventor recently succeeded in having one patented. On November 1 Boris Volfson of Huntington, Indiana, received U.S. Patent 6,960,975 for his design of an antigravity space vehicle.

A perpetual-motion machine may defy the laws of physics, but an Indiana inventor recently succeeded in having one patented. On November 1 Boris Volfson of Huntington, Indiana, received U.S. Patent 6,960,975 for his design of an antigravity space vehicle.

Volfson’s craft is theoretically powered by a superconductor shield that changes the space-time continuum in such a way that it defies gravity. The design effectively creates a perpetual-motion machine, which physicists consider an impossible device.

Journalist Philip Ball reported on the newly patented craft in the current issue of the science journal Nature.

Robert Park, a consultant with the American Physical Society in Washington, D.C., warns that such dubious patents aren’t limited to the antigravity concept.

“I might hear a complaint about a particular patent, and then I look into it,” he explained. “More often than not it’s a screwball patent. It’s an old problem, but it has gotten worse in the last few years. The workload of the patent office has gone up enormously.”

Some people might consider patents on unworkable products to be relatively harmless. Park, a physics professor at the University of Maryland at College Park, disagrees.

“The problem, of course, is that this deceives a lot of investors,” he said. “You can’t go out and find investors for a new invention until you can come up with a patent to show that if you put all this money into a concept, somebody else can’t steal the idea.

“[Approving these kind of patents can] make it easier for scam artists to con people if they can get patents for screwball ideas.”

Perpetual questPerpetual-motion machines have long held special appeal for inventors—particularly during the concept’s heyday around the turn of the 20th century.

Patent applications on such devices became so numerous that by 1911 the patent office instituted a rule that perpetual-motion machine concepts had to be accompanied by a model that could run in the office for a period of one year.

“The patent office used to say that they didn’t patent perpetual-motion machines, but it turned out that there really was no such rule,” Park said.

A 1990 federal court ruling against inventor Joe Newman, who applied for a patent on a motor that he said could return more energy than it consumed, was interpreted as precluding patents for such devices.

But the verdict has not fully stemmed the tide of applications.

“The effect that [the court ruling] has had is that patent seekers no longer call them perpetual-motion machines,” Park said. “Now it’s called capturing zero-point energy.”

Zero-point energy is a real type of energy produced by the miniscule movements of molecules at rest. Harnessing this energy is theoretically possible, but the task seems, at least for the moment, practically impossible.

Patent reviewWhen asked about Volfson’s machine, a U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) spokesperson said the agency does not discuss specific patents. But the spokesperson explained that qualified patent examiners review each application according to rigid criteria.

First the idea must be patentable by law, said Brigid Quinn of the USPTO, based in Alexandria, Virginia. “There is patent law that describes what is patentable subject matter—for example, the laws of nature aren’t patentable.”

If an idea passes legal muster it must then meet several specific criteria.

“Is it new?” Quinn asked. “Is it useful, which means does it work? Is it nonobvious? And is it described in such detail to enable someone skilled in that technology to make and use it based on the description that must accompany the application?”

Patent office scientists and engineers, skilled in particular technologies, make their determinations based on these criteria and the current state of the science involved.

But despite their best efforts, mistakes are inevitable and patents may be granted to unworkable ideas. Some 5,000 examiners must currently handle a load of 350,000 applications per year.

Meanwhile, no amount of nay-saying will stop inventors from dreaming of a legitimate perpetual-motion breakthrough. Park believes that these hopefuls far outweigh any ill-meaning scammers.

“The most curious aspect of this is that most of these people truly believe that they’ve made some new discovery that most people haven’t thought of,” he said. “It doesn’t often work out.”